2025-12-30

Introduction

The community of Azerbaijanis in Georgia studied in this research can be called a community of practiceExternal link, which broadly refers to a specific kind of social network characterised by mutual engagement, a jointly negotiated enterprise, and a shared language repertoire. They are recognised as an ethnic minority comprising 6.3% of the total population (233,000 people). They have been living in Georgia, particularly the southeast parts, since the early Middle Ages. As users of the language belonging to the Turkic family of languages, in the search for their roots, Azerbaijanis refer to the history of groups using similar languages and living in Georgia or its adjacent areas, like for example Azerbaijan or Turkey. Thus, ethnic diversity in southeast Georgia has its origin in the Middle Ages, when the great migration of Turkic people from Central Asia to the Caucasus and Persia changed the existing ethnic structures. In the Soviet times the discrepancy between the legal and de facto status of Russian and Georgian led to a paradoxical situation: proficiency in Georgian was compulsory only for the titular nation, ethnic Georgians. Although minority groups were required to learn Georgian, teaching was very formal and students were hardly motivated. Most of them learned either in Russian or in their mother tongue.1 Today, while Georgian is the language of social advancement and the official language of the state, Azerbaijani is also important and can be seen in the local, grassroots linguistic landscape. Other languages with growing popularity are Turkish and English. Azerbaijani is spoken by different ethnic groups in Shulaveri, and is in a way, an informal lingua franca.

Methodology

In this blog I focus primarily on analysing the linguistic landscape of Shulaveri (Marneuli municipality, Kvemo Kartli region, located in southeast Georgia) and the surrounding area in order to show how different language users construct the spaces where their languages are present, both materially and symbolically. Since 2018, I was regularly taking pictures of different types of inscriptions in several alphabets and languages. For the purpose of this article, I decided to analyse 60 of them. However, having been in the field since 2015, I became accustomed to the existence of different types of languages, alphabets and inscriptions, so after some time I would stop paying attention to the differences of alphabets and languages, as long as I could read and understand them. Often it was only when analysing the photographs I have taken that the dynamics of space, the transformation of places, the disappearance of some and the appearance of new ones revealed themselves to me. Therefore, I wanted to better understand this dynamic process and examined it in order to show how sharing and negotiating the linguistic landscape in Shulaveri is related to the identities of its dwellers.

What is linguistic landscape (LL)?

The linguistic landscape is basically all the linguistic objects that mark public spaceExternal link. These can include road and street signs, commercial/private and institutional signs, names of places, streets, buildings and institutions, billboards, but also the language used on personal objects that have a 'public function', such as, for example, business cards. They are often symbolic markers revealing the power relations and status of linguistic communities in a given territory and of linguistic territories, thus sometimes serving as ethnic boundaries inside the communities.2 This side of linguistic diversity is important for showing how languages function in a concrete, materialised space, but we should not omit the language use in different communicative situations. The presence of languages becomes apparent not only in visual, but also in oral communication. In multilingual regions, particularly in communities of origin or migrants, the co-presence of different languages, code-switching, and code-mixing takes place. In the research field, I repeatedly observed the intermingling of several languages – Azerbaijani, Turkish, Russian, Armenian, Georgian and English – although they belong to several different language families and are used by people who often identify them with the given ethnicity. In shops and local markets/bazaars, most vendors in Shulaveri use Azerbaijani, but generally, communication also takes place in Russian and Georgian, depending on the respective linguistic competence of a particular vendor and clients. Wholesale markets have the ability to regulate inter-ethnic relations. The example of Marneuli shows that the common-use of selling and buying spaces allows the multilingual population to communicate with each other on a daily level – all the more so after the closure of the famous multi-ethnic market in Sadakhlo, which operated on the Georgian-Armenian border until 2005 and was closed after pressureExternal link from both the Georgian and Armenian governments.

Language of/on plaques and other inscriptions

Signboards exist in several alphabets and languages – Azerbaijani in the Latin alphabet (sometimes also in Cyrillic as it was used during the Soviet period), Russian with Cyrillic, and Georgian with its own alphabet Mkhedruli, sometimes both Cyrillic Russian and Mkhedruli Georgian although rarely, and in some places also, although quite rarely – if the building is managed by an Armenian-speaking person – in Armenian, but not necessarily. There are also three additional languages – English, Turkish, and Arabic. We can differentiate between “traditional local lingua franca” languages, like Georgian, Azerbaijani, Armenian, Russian, and additional locally important languages, like Turkish and more internationally understandable languages like English and Arabic. Some signs change quite frequently when a new owner of a particular building appears, or when the type of business changes. Many of them are also faded and left unattended on buildings. They bring to mind that they would lend themselves to a diachronic study of signs in the spirit of Jan Blommaert'sExternal link concept of analysing how they have changed over the years. For religious use, there is also the Arabic language and alphabet, which appears mainly on cemeteries and in the surrounding mosques, for instance on inscriptions inside them, information plaques about the year of construction, the patron or founder, and on fences in the form of banners with religious slogans. Mosques also have religious schools (madrassas) in which Arabic is taught alongside state school curriculum.

Inscriptions in English are becoming more popular. In the city of Marneuli, billboards are hung over the streets to communicate official information (e.g. on the occasion of holidays, election or social campaigns, such as those related to information about the COVID-19 pandemic) or as a place to advertise health clinics. Official slogans are always created in only two languages – Azerbaijani and Georgian.

The election posters distributed in the district are always bilingual in Azerbaijani and Georgian. Therefore, it can be considered that these two languages at the official level are predominant in the examined area, while private inscriptions are also in Russian. Yet, the only truly official language is Georgian.

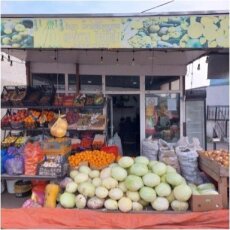

On pictures 1-3 we can see examples of plaques in three languages – Georgian, Azerbaijani and Russian

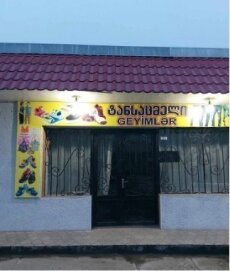

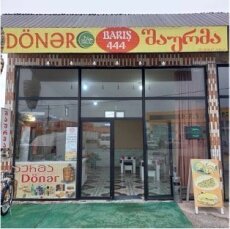

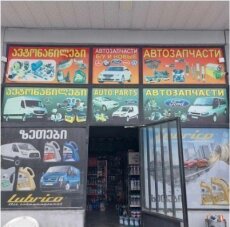

Pictures 4-6 show plaques with Azerbaijani and Georgian languages

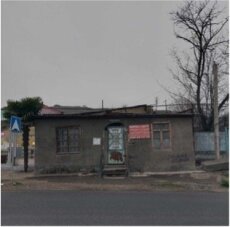

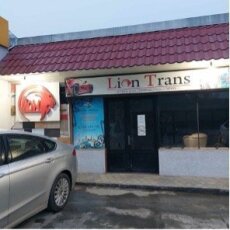

Georgian and Russian can be found next to each other on examples of plaques on pictures 7-10

On pictures 11-12 we can observe the coexistence of Georgian and Armenian languages, while on picture 12 we can also see the neighbouring signboard with the advertisement of the hairdresser in Azerbaijani. Pictures 13-14 tell us something about the new tendency – in recent years English, with the growing popularity, started to appear next to Georgian, discarding Russian as the new “international tool of communication”, while on pictures 15-17 we can see both languages together next to Georgian. Sometimes Georgian, Armenian and Russian can co-exist on one plaque, as we can see on picture 18. The combination of Georgian, English and Russian can be found on the plaque from picture 19. Pictures 20 and 21 are quite specific, rare examples of using Turkish together with Georgian and of using only Georgian as well.

Place names (toponyms)

I would also like to touch on a topic related to toponyms, also known as proper names of places, so for this purpose I will introduce the historical context of place, which in some way explains the multilingual discourse I have observed. Toponyms are an integral part of the linguistic landscape, and their top-down change is a common phenomenon during various types of political transition. In the case of Georgia, this primarily involves several shifts in power and the symbolic appropriation of the linguistic landscape by a particular group, as well as symbolic appropriation, represented by the top-down imposition of symbols such as crosses, which are erected in some Kvemo Kartli villages, regardless of the religion of their inhabitants.

The changes in proper names can be traced back to the approval of the new USSR constitution in 1936, which recognised Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia as separate union republics within the USSR. Administrative and territorial division began then, including the drawing of topographical maps to establish borders. In the 1940s, the process of toponymic changes began, especially in the areas bordering the Armenian SSR and the Azerbaijani SSR. Among others, the name of Borchalo was then changed to Kvemo Kartli, Sarvan to Marneuli, Luxembourg to Bolnisi, and Bashkichenti (or Bashkenti) to Dmanisi. Further, broader changes continued in the 1990s. In 1993, the then head of state, Eduard Shevardnadze, introduced a law that approved some of the new place names translated from Azerbaijani to Georgian or changed to names close to the Georgian language,3 although their “Georgianisation” had already taken place in 1990-1991. Despite this, many former place names are still used in Azerbaijani-populated areas, even though they cannot be found either in official documents or on maps. It has sometimes been a bit of a handicap for me, too, when, in conversations with locals, I have heard a place name that no longer existed administratively. An example of such a name is the town of Ponichala located at the exit from Tbilisi towards Marneuli, which is called Sabana by AzerbaijanisExternal link.

As some researchers point outExternal link, in border territories the meaning of proper names (and words in general) is complex. This is due to the multiplicity and diversity of customs of the people who inhabited these places, which is reflected in proper names, sometimes functioning in unofficial spaces. It should be emphasised that toponyms have an important identifying function also for the culture of a national minority, like for instance influencing consciousness through messages they sendExternal link. The symbolic function of the linguistic landscape created by toponyms may be stronger in communities where the native language is the most important dimension of ethnic identity. In this respect, too, the Azerbaijani language is neglected in Georgia’s language policy. As I could observe, it is still a lively topic in the Azerbaijani community in Georgia. Initiatives taken to highlight difference thus become the subject of an identity narrative and can lead to the politicisation and ethnic mobilisation of particular communities, as it is visible in the example of the Azerbaijani community in Shulaveri.

Conclusions

According to my conversations with residents of the area and several years of field observations I could see that the presence of the Azerbaijani and Georgian languages in the public space of Shulaveri is important for residents who identify themselves as Azerbaijanis and Georgians, but using Armenian language on signboards is not necessarily principal for native speakers of Armenian. Russian language is still used as local informal lingua franca, so often it is displayed together with other languages. It seems to be quite important that there are almost no signboards with Georgian as the only language featured on them. Also, in many cases, the Azerbaijani language is written in Latin scripts in public spaces, and is therefore readable and understandable by people who otherwise do not know the language. My observations on languages in the area allowed me to see language representations in the local space, grasping the perspective of its dynamic and change over time. At the same time, Azerbaijani is almost not visible at the formal, official level – it only functions during temporary initiatives, for example by being present on election posters used by local politicians or occasional banners ordered by local authorities. For this reason, I believe that this kind of activity has two functions – the first is the instrumentalisation of the use of the language for electoral support and the second is a certain exoticisation of the Azerbaijani minority, linguistically noticed several times a year only during specific events or holidays (like Novruz or Kurban Bayram). Other languages visible in the linguistic landscape are Armenian, Russian, Turkish, Arabic, and English. In any case, local signs are used as a medium to communicate, symbols of identities as well as markers of differences.

Author Bio: Dr. Klaudia Kosicińska, Postdoctoral Fellow and Anthropologist, Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography and the Migration Research Center of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. In 2023 she defended her PhD entitled, "Everyday life between borders. Mobility, translocal practices and neighbourhood in southeast Georgia" at the Institute of Slavic Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences.

Peer reviewed by: Prof. Dr. Diana Forker, Project Leader and Principal Investigator, Institute for Caucasus Studies, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena

[1] Gabunia, Kakha and Ketevan Gochitashvili. 2019. “Language policy in relation to the Russian language in Georgia before and after dissolution of the Soviet Union.” The soft power of the Russian language. Pluricentricity, politics and policies, edited by A. Mustajoki, E. Protassova, M. Yelenevskaya, 37-45. London: Routledge.

[2] Spolsky, Bernard and Robert L. Cooper. 1991. The Languages of Jerusalem. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

[3] Sometimes, the acquisition of a Georgian-sounding name was created by adding the suffix “i” to the nominative, adequate to the grammar rules of Georgian. My research shows that one type of change is a direct translation of a name from the local language into Georgian, as in the case of the village of Kvemo Sarali (formerly: Yukhari Saral), the other type of change is a complete renaming, as in the case of Talaveri (formerly: Fakhrally), Savaneti (formerly: Imir-Asan) or Chapala (formerly: Kochulu) in Bolnisi. There are also names whose names have been modified in a different way, as in the case of Amamlo (formerly Hammamly) in Dmanisi Municipality.

-

Picture 1- A local vegetable shop, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 2 - A meat shop, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 3 - Bakery, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 4 - Clothes shop, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 5 - Shop with auto parts and supplies with the message in two languages saying- %22Sold items won’t be taken back! Items bought on credit won’t be exchanged for other ones!”, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 6 - Kebab bar, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 7 - Welding services, Shulaveri

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 8 - For sale, Shulaveri, Georgia, March

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 9 - A local pharmacy, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 10 - Car service, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 11 - An Armenian supermarket, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 12 - Closed bakery and barber shop

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 13 - A gas station, Shulaveri

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 14 - Flower shop and kebab bar, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 15 - Chemical products shop

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 21 - Discount shop with doors and windows, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 16 - Auto parts shop, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 17 - A vet shop, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 18 - Auto parts shop, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 18 - Auto parts shop, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska -

Picture 20 - Bakery, Shulaveri, Georgia, March 2024

Image: Klaudia Kosicińska

How to contribute to the Across the Caucasus Blog

The blog is open to anyone who is interested and informed in writing about contemporary developments in the Caucasus and the wider Black Sea and Caspian Sea region including but not limited to scholars, researchers, freelance writers, activists, artists, civil society members, and politicians. Young female researchers and researchers from the Caucasus countries are particularly encouraged to submit their articles. You will find a detailed list of possible topics and the blog guidelines on the website. Before you send your work to us, please make sure to familiarize yourself with our guidelines. If you are not sure whether your topic fits our thematic scope or have another question related to the blog, feel free to contact us at jenacauc@uni-jena.de and indicate “Across the Caucasus Blog” in the subject line.