The Caucasian war, which ended in 1864 with the Russian conquest of the Caucasus and the mass murder, ethnic cleansing, and expulsion in particular of the Circassians, forced a huge part of the West Caucasian population to flee to the Ottoman Empire. Thus, today Circassians, Abkhaz but also Chechens and other ethnic groups from the Northern Caucasus live in Turkey, Jordan, Syria, Israel and some other places in the Near East. Jordan is perhaps the country in which the Caucasian diasporas enjoy the greatest freedom and the highest esteem.

What is the sociolinguistic situation of the Circassians and Chechens in Jordan today? In order to achieve a better picture of the two communities I visited Amman for a week in December 2021 and interviewed a number of Chechens and Jordanians (Figure 1).

The Circassians of Jordan

The first wave of Circassians arrived in Jordan in 1878 and until 1906 more and more immigrants followedExternal link. Some of them settled in and around the Roman theatre in the center of Amman (Figure 2) and can thus be considered to be the first indigenous population of Amman in its modern times (Al-Wer 1999). Circassians divide themselves into twelve tribes. The tribal division partially corresponds to dialectal differences. The vast majority of Circassians in Jordan belong to one of four tribes (Shapsug, Abzakh, Bzhedug and Kabardian).

Since the establishments of the Emirate of Transjordan in 1921, which became the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan in 1946, Circassians have a close relationship with the royal Hashemite family and serve as guards of the royal family.External link They mostly belong to the urban middle class and work in the government bureaucracy and military. Together with the Chechens they have representatives in the parliament and in executive branches of the government,External link which demonstrates their high social status (Jaimoukha 2001). The number of Circassians currently living in Jordan is not easy to estimate. Sources vary between 30,000 up to 100,000External link (e.g. Bram & Shawwaf 2019,External link Jaimoukha 2001).

Circassians are actively involved in the political and social-cultural life of Jordan. The Circassian Charity Association was founded in 1932 and it is the second oldest charity association in Jordan. It was established for supporting Jordanian Circassians, for educational and cultural purposes, as a meeting point and club for elders and youth (Figure 3). It hosts a library, an archive and multi-purpose halls used for dancing lessons and youth activities. During my visit to the Association, I met with the current president, Prof. Dr. Ibrahim Varouqa (Figure 4), who introduced me to other members of the association and reported that the association reaches around half of the Circassian population in Jordan (Figure 5). The association has eight branches in various quarters of Amman and other settlements including a Lady’s branch (Figure 6). The latter runs the Prince Hamza School (Figure 7) and a kindergarten (Figure 8). Other organizations are the Al-Ahli ClubExternal link (Figure 9), a sports clubExternal link, that was established in 1944 and has since then been operating very successfully, and the social, cultural and sports club Al-Jeel Al-Jadeed ClubExternal link, which was established in 1950. The International Circassian Cultural AcademyExternal link, ICCA was founded in 2010 (Figure 10). Its aim is the preservation and the promotion of the Circassian cultural heritage, and therefore it offers Circassian language courses and has published an Arabic-Circassian dictionary (Figure 11).

Jordanian Circassians identify themselves as Circassians and Jordanians at the same time and these identities are not in a contradictory relationship. To be a Jordanian does not mean to belong to specific ethnic group, but to be a loyal citizen of the Jordanian kingdom and to share a common religion – Islam –, which is not tied to any national or ethnic community but to the Ummah. Circassians in Jordan are Muslims, have built a couple of mosques, among which the Abu Darweesh MosqueExternal link is one of the most famous mosques of Amman (Figure 12), and they view Jordan as an Islamic country (Figure 13). In their narratives and for their ethnic identity, the genocide and the Caucasian homeland play important roles and they have manifold links to the Caucasus. Some Circassians as, for instance, Prof. Dr. Ibrahim Varouqa, have studied in the Caucasus (e.g. in Nalchik) during the late Soviet Period and later founded an Alumni Group in Amman. Some even moved there after the break-up of the Soviet Union, sometimes supported by the Circassian Repatriation OrganizationExternal link. But the majority prefers to stay in Jordan (or to migrate to other countries than the Russian Federation, which does not really welcome new immigrants).

With respect to language knowledge and use, a constant language shift has been observed since the first sociolinguistic studies by Al-Wer (1999) and Dweik (1999) more than 20 years ago. The latest studies by Rannut (2009, 2011) found that among the more than 300 students of the Circassian school, 72% used only Arabic at home, 6.5% used only Circassian, and 15% used Circassian in addition to Arabic as a second language (Figure 14). Rannut’s data also show that age is the main indicator for language use. The older the interlocutor is the more likely it is that s/he will be addressed in Circassian. And vice versa, the older the speaker herself/himself is the better is her/his command of Circassian.

At Prince Hamza SchoolExternal link, only East Circassian, i.e. standard Kabardian, is taught. According to personal interviews with young Circassians, such as Adam Ishaqat Halashta (Адэм Исхьакъат Хьэлащтэ), this has been and continues to be problematic for two reasons. First, the majority of the current students are considered semi-speakers or even non-speakers that, second, come from a background or live within a speech community that is dominated by western dialects (mostly Bzhedug, but to a lesser degree also Shapsug or Abzakh). The school currently has three teachers, two from the Caucasus and one from Syria, who teach all students in all grades (Figure 15). In the kindergarten there are also language classes. The school is a private school that is, in principle, open to everyone. All students have to participate in the language classes. There are very few Arabic students attending the school who are also learning Circassian. Students do not receive grades in the Circassian classes and the number of hours per week is very little. Language classes mostly focus on reading and writing such that students of the Circassian school have a better proficiency in written Circassian than in spoken Circassian (see also Rannut 2009). Books and other materials have been imported from Kabardino-Balkaria and thus employ the Cyrillic alphabet for Kabardian. Many teaching materials are outdated and the teachers have to prepare their own.

The Chechens of Jordan

Chechens began to settle in Jordan in 1901/1902. They established a few settlements and today mainly live in four villages or small townsExternal link (Zerka/Zarqa, Sweileh, Al-Suhknah / Sukhneh, and Al-Azraq/Chechen-Azraq/Alazaraq Al-Janooby), relatively close to the Circassian settlements in and around Amman that were established some twenty years earlier. Many Chechens of Jordan live close in a neighborhood with other Chechens, and only 30 to 40 years ago Chechen children still grew up mainly speaking Chechen with their family members, friends and neighbors. In Sweileh, a district of Amman where many Chechens live, the mosque was built by ChechensExternal link in 1920 to 1922 (Figure 16).

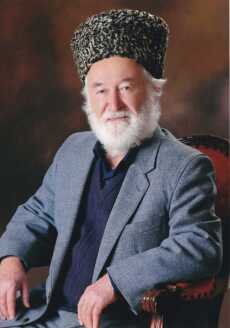

During my field trip I met Ahmad, the son of Isam (Sami) Bino. Isam Bino (Figure 17) is a famous representative of the Chechen communityExternal link in Jordan who created a small museum in his house in Sweileh.External link This museum hosts some objects of Chechen culture of which the oldest have been brought to Jordan from the Caucasus by the first Chechen settlers (Figure 18).

Estimations of the Chechen community in Jordan vary between around 9,000External link and 15,000 (Jaimoukha 2005: 238). In a personal interview a community member estimated the number at about 12,000. Many Chechens from Jordan have visited their homeland in the Caucasus and a few have even moved there. However, the vast majority of the Chechens does not have intentions to leave Jordan for the historical homeland.

By Jordanians, Chechens and Circassians are considered as one group. Just like as the Circassians, many Chechens work for the government, the army and public security. Together with Circassians, they have their own representatives in the Jordanian parliament and traditionally have a close relationship with the ruling Hashemite family. Chechens established their own cultural centers, associations and clubs, councils, magazines, etc. albeit on a somewhat smaller scale than Circassians because their community is smaller.

The Chechen-Ingush Association in Sweileh hosts, among other things,External link a swimming pool and a big hall in which Chechens celebrate weddings and other important events (Figure 19). According to community members, women in particular are very active in the association and regularly organize social events.

The most detailed sociolinguistic study of the Chechen community in Jordan by Dweik (2000) is based on interviews with 100 Chechens (age 10 to 59) of the third- and fourth-generation. He shows that today basically all Chechens are bilingual. Chechen is in a diglossic relationship with Arabic and almost exclusively used as an oral language. The major functional domains of Chechen are private situations within the family, among friends and relatives, in the neighborhood, at school and in the market place. In general, the Chechens of Jordan have largely maintained their language and culture. According to Dweik (2000) this is due to the tight social networks among community members and residential closeness, which allows daily interactions, resistance to ethnically mixed marriages, and a positive attitude towards the Chechen language and culture and the original homeland, which serve as strong identity markers. My own observations largely confirm the study. Chechens often marry within their community or with Circassians. The majority of them speak Chechen at home and with other Chechens. Yet, there are more and more families in which Arabic is used on a daily basis and children of those families are Arabic-dominant even before they enter kindergarten or school. The only official language in Jordan is Arabic and Chechen is exclusively used as an oral language. Some Chechens organize private classes for teaching the Cyrillic alphabet that is used in the northern Caucasus.

Language and identity of the Chechens and Circassians in Jordan

With the help of a questionnaire, I interviewed members of the Chechen and Circassian communities. I asked about their ethnic identity and attitudes towards their languages and cultures vs. Jordanian Arabic language and culture.

In both communities the symbolic value of language is very high in the sense that the native language is central for the identity. Similarly, a good command of the minority language is regarded as being very important. However, young Circassians from Jordan normally do not speak the language anymore because the large majority of their parents and partially even grandparents’ generation did not speak Circassian to their children. By contrast, most young Chechens speak Chechen. We thus observe a puzzling sociolinguistic situation: the smaller ethno-linguistic group – the Chechens – who seemed to be more open to mixed marriages 20 years ago (according to Al-Wer 1999) and has less resources with regard to education / language teaching, has preserved the language better than the larger group, the Circassians. Both communities have many similarities with respect to social class and position in the majority society, cultural and social norms, migration history and language attitude. Nevertheless, the differences in language knowledge and use are striking, and there are several reasons for that. The first Circassians arrived some 20 years earlier and thus a language shift among the Chechens might simply be delayed. This explanation was suggested by a young Circassian activist and, in general, during 20 years is almost a period of time that gives birth to a new generation that might has changed patterns of language use. However, there is still no pronounced language shift within the Chechen community to the same degree as it had already been observed in the Circassian community in 1995 by Al-Wer. A more decisive reason seems to be that the early compact settlements of Circassians were broken up through the influx of new immigrants, in particular Palestinians who arrived between 1947 and 1967, e.g. in the city center of Amman and in other parts of Amman such as Wadi as-Seer. Furthermore, following the Gulf War in the 1990s the most significant urban boom that began and from a sociolinguistic point of view urbanization normally leads to massive language shifts to dominant languages, which is Arabic in this case.

By contrast, many Chechens still live comparatively closely together in the rural areas of Al-Suhknah and Al-Azraq where networks are tighter than in Sweileh (today a district of Amman) and Zarqa, the second largest city of Jordan (Al-Wer 1999). Al-Suhknah and Al-Azraq are relatively isolated and not heavily affected by urbanization. In fact, in my interviews it turned out that “living amongst people of your ethnic group” is slightly more important for Chechens than for Circassians. In addition, as Adam Ishaqat Halashta pointed out to me that in Al-Suhknah and Al-Azraq mainly live settled, urbanized Bedouins and the cultural differences with the Chechen community might have prevented mixed marriages. Al-Azraq also hosts a noticeable amount of Druze, whom Chechens have no marital relations with due to religious differences.

Al-Wer (1999) also hypothesizes that the traditional social organization and current differences in social structures have led to diverging levels of assimilation. Traditionally Chechens have an “egalitarian structure with a non-hereditary unified leadership, which helped to maintain the unity of the group in the new social and political contests.” By contrast, the traditional social system of the Circassians is hierarchical and this, according to Shami (1982) and Al-Wer (1999), weakened ethnic cooperation and a sense of unity among them. It accelerated competition between elites, assimilation to the majority society and thus sped up language shift.

In my interviews it turned out that Chechens have a slightly higher preference for a so-called ‘hybrid identity style,’ which permits the simultaneous identification with multiple cultural identities instead of an ‘alternating identity style’External link in which different components of identity and behavioral repertoires are alternatingly emphasized depending on the context. For instance, all Chechens but not all Circassians whom I interviewed agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I see myself as a culturally unique mixture of Jordanian and Chechen/Circassian”, which is in accordance with the hybrid identity style. By contrast, Circassians more strongly than Chechens agreed with the statement “I alternate between being Jordanian and Circassian/Chechen depending on the circumstances” that explicates an alternating identity style. It seems that Chechens manage better to preserve their language because they tend to merge both cultures and languages, which is evidenced by the fact that code switching is a widespread practice. Circassians, by contrast, have a somewhat greater preference for keeping languages and cultures apart. Thus, the generation of Circassians who are today in their 50s or older preferred to speak Arabic to their children while they continued to speak Circassian among themselves.

-

Figure 1: Interviews with Circassian Youth at the Circassian Charity Association, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

-

Figure 2: The Roman theatre of Amman, one of the original places of the Circassians in Jordan, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

-

Figure 3: Circassian Youth after a dance class at the Circassian Charity Association, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

-

Figure 4: Prof. Dr. Ibrahim Varouqa, president of the Circassian Charity Association, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 4: Prof. Dr. Ibrahim Varouqa, president of the Circassian Charity Association, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 5: Meeting room at the of the Circassian Charity Association, AmmanImage: Diana Forker

Figure 5: Meeting room at the of the Circassian Charity Association, AmmanImage: Diana Forker -

Figure 6: Branch of the Circassian Charity Association in Wadi as-Seer, a district of Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 6: Branch of the Circassian Charity Association in Wadi as-Seer, a district of Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 7: Prince Hamza School, the Circassian private school of Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 7: Prince Hamza School, the Circassian private school of Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 8: Circassian Kindergarten, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 8: Circassian Kindergarten, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 9: Adam Ishaqat Halashta and the author (Diana Forker) in front of the Circassian Al-Ahli Club, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 9: Adam Ishaqat Halashta and the author (Diana Forker) in front of the Circassian Al-Ahli Club, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 10: Circassian activists at the International Circassian Cultural Academy, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

-

Figure 11: Class room for language classes at the International Circassian Cultural Academy, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 11: Class room for language classes at the International Circassian Cultural Academy, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 12: Abu Darweesh Mosque, built by Circassians in 1961, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 12: Abu Darweesh Mosque, built by Circassians in 1961, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 13: Interior of the Circassian mosque in Wadi as-Seer, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 13: Interior of the Circassian mosque in Wadi as-Seer, December 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 14: Welcome sign in Arabic, Circassian and English in the Prince Hamza School, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

-

Figure 15: Circassian teachers of the Prince Hamza School, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 15: Circassian teachers of the Prince Hamza School, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 16: Sweileh and the Chechen mosque at night, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 16: Sweileh and the Chechen mosque at night, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 17: The Chechen Elder and Activist Isam (Sami) Bino, who passed away in 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 17: The Chechen Elder and Activist Isam (Sami) Bino, who passed away in 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 18: The private Chechen museum of Isam (Sami) Bino in his house in Sweileh, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 18: The private Chechen museum of Isam (Sami) Bino in his house in Sweileh, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker -

Figure 19: The Chechen-Ingush Association in Sweileh, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Figure 19: The Chechen-Ingush Association in Sweileh, Amman, December 2021Image: Diana Forker

Links

The Sweileh mosque build by Chechens (two parts, in Arabic)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-3MdzIxBcN4External link

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2BfMmLr0qcQExternal link

References

Bram, Chen and Yasmine Shawwaf. 2019. Circassians. In P. R. Kumaraswamy (ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore, 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9166-8_6

Dweik, Bader S. 2000. Linguistic and cultural maintenance among the Chechens of Jordan. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 13(2). 184–195.

Dweik, Bader. 1999. The language situation among the Circassians of Jordan. Albasaer, 3 (2), 10-28.

Jaimoukha, Amjad. 2001. The Circassians: A handbook. New York: Palgrave.

Jaimoukha, Amjad. 2005. The Chechens: A handbook. London: Routledge Curzon.

Rannut, Ulle. 2009. Circassian language maintenance in Jordan, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 30:4, 297-310, https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630902780723

Rannut, Ulle. 2011. Maintenance of the Circassian Language in Jordan. IRI Language Policy Publications.

Shami, Seteney. 1982. Ethnicity and Leadership: The Circassians in. Jordan. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. Berkeley: University of California.

Autor Bio

Prof. Dr. Diana Forker, Project Leader and Principal Investigator, Institute for Caucasus Studies, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena

Peer reviewed by:

Adam Ishaqat Halashta, German Jordanian University, Amman

Pictures

(all pictures by Diana Forker)

Figure 1: Interviews with Circassian Youth at the Circassian Charity Association, Amman, December 2021

Figure 2: The Roman theatre of Amman, one of the original places of the Circassians in Jordan, December 2021

Figure 3: Circassian Youth after a dance class at the Circassian Charity Association, Amman, December 2021

Figure 4: Prof. Dr. Ibrahim Varouqa, president of the Circassian Charity Association, Amman, December 2021

Figure 5: Meeting room at the of the Circassian Charity Association, Amman

Figure 6: Branch of the Circassian Charity Association in Wadi as-Seer, a district of Amman, December 2021

Figure 7: Prince Hamza School, the Circassian private school of Amman, December 2021

Figure 8: Circassian Kindergarten, Amman, December 2021

Figure 9: Adam Ishaqat Halashta and the author (Diana Forker) in front of the Circassian Al-Ahli Club, Amman, December 2021

Figure 10: Circassian activists at the International Circassian Cultural Academy, Amman, December 2021

Figure 11: Class room for language classes at the International Circassian Cultural Academy, Amman, December 2021

Figure 12: Abu Darweesh Mosque, built by Circassians in 1961, Amman, December 2021

Figure 13: Interior of the Circassian mosque in Wadi as-Seer, December 2021

Figure 14: Welcome sign in Arabic, Circassian and English in the Prince Hamza School, Amman, December 2021

Figure 15: Circassian teachers of the Prince Hamza School, Amman, December 2021

Figure 16: Sweileh and the Chechen mosque at night, Amman, December 2021

Figure 17: The Chechen Elder and Activist Isam (Sami) Bino, who passed away in 2021

Figure 18: The private Chechen museum of Isam (Sami) Bino in his house in Sweileh, Amman, December 2021

Figure 19: The Chechen-Ingush Association in Sweileh, Amman, December 2021

Download as PDFpdf, 147 kb · de

How to contribute to the Across the Caucasus Blog

The blog is open to anyone who is interested and informed in writing about contemporary developments in the Caucasus and the wider Black Sea and Caspian Sea region including but not limited to scholars, researchers, freelance writers, activists, artists, civil society members, and politicians. Young female researchers and researchers from the Caucasus countries are particularly encouraged to submit their articles. You will find a detailed list of possible topics and the blog guidelines on the website. Before you send your work to us, please make sure to familiarize yourself with our guidelines. If you are not sure whether your topic fits our thematic scope or have another question related to the blog, feel free to contact us at jenacauc@uni-jena.de and indicate “Across the Caucasus Blog” in the subject line.